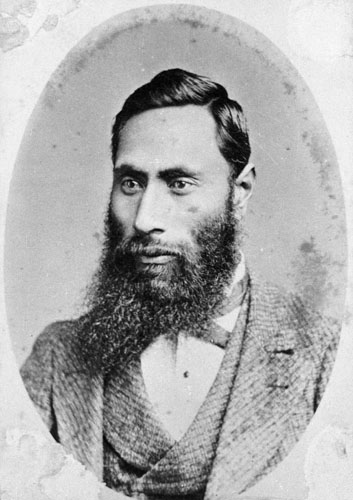

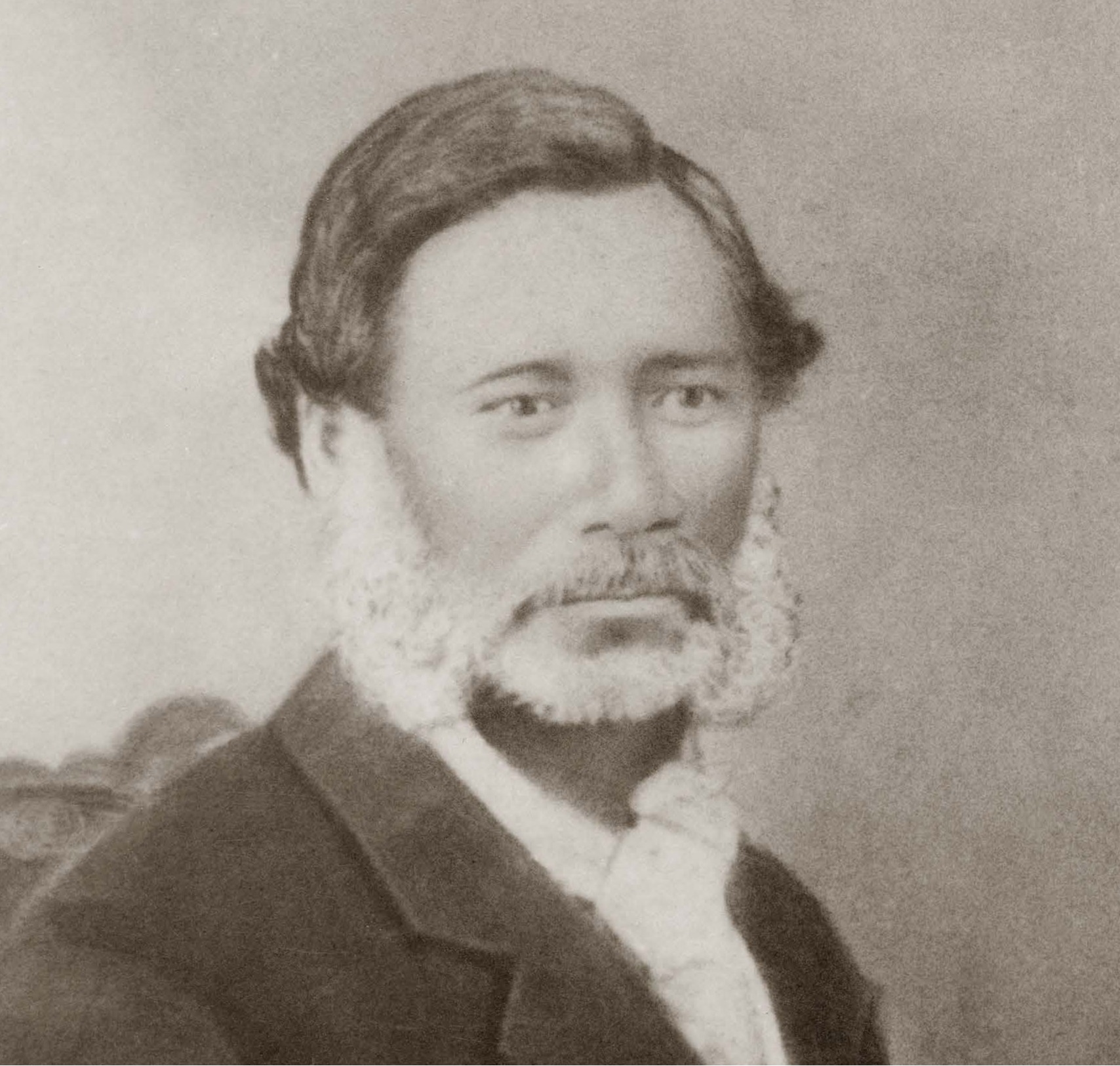

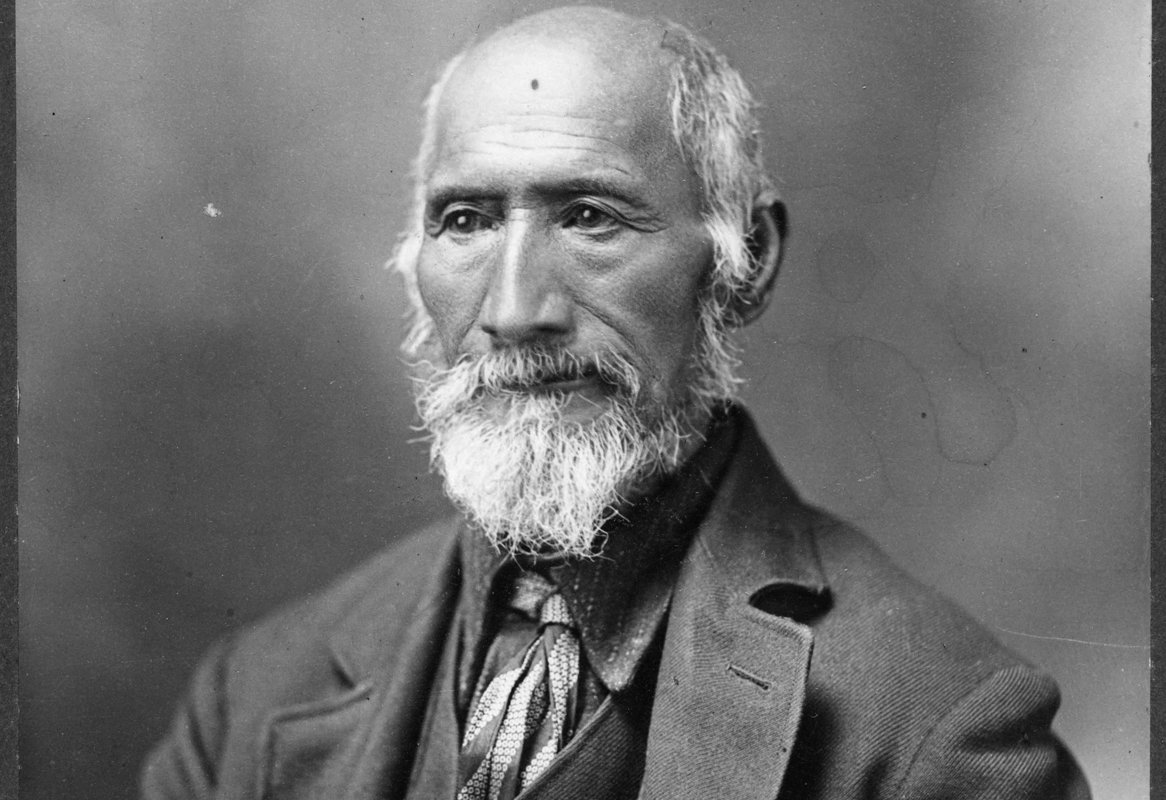

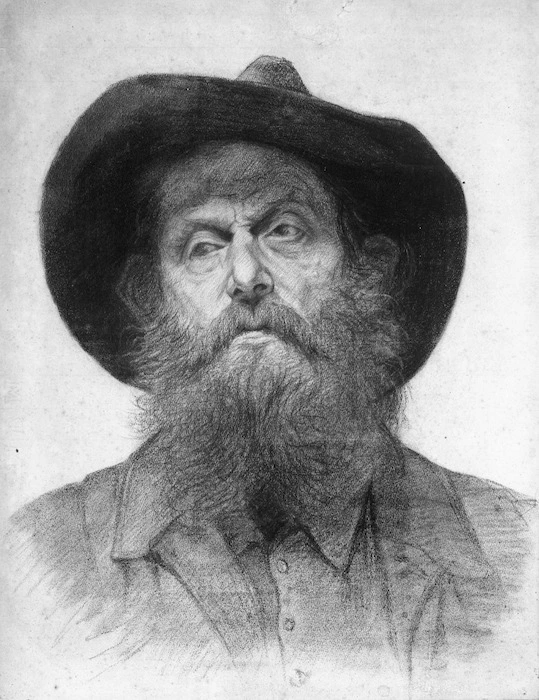

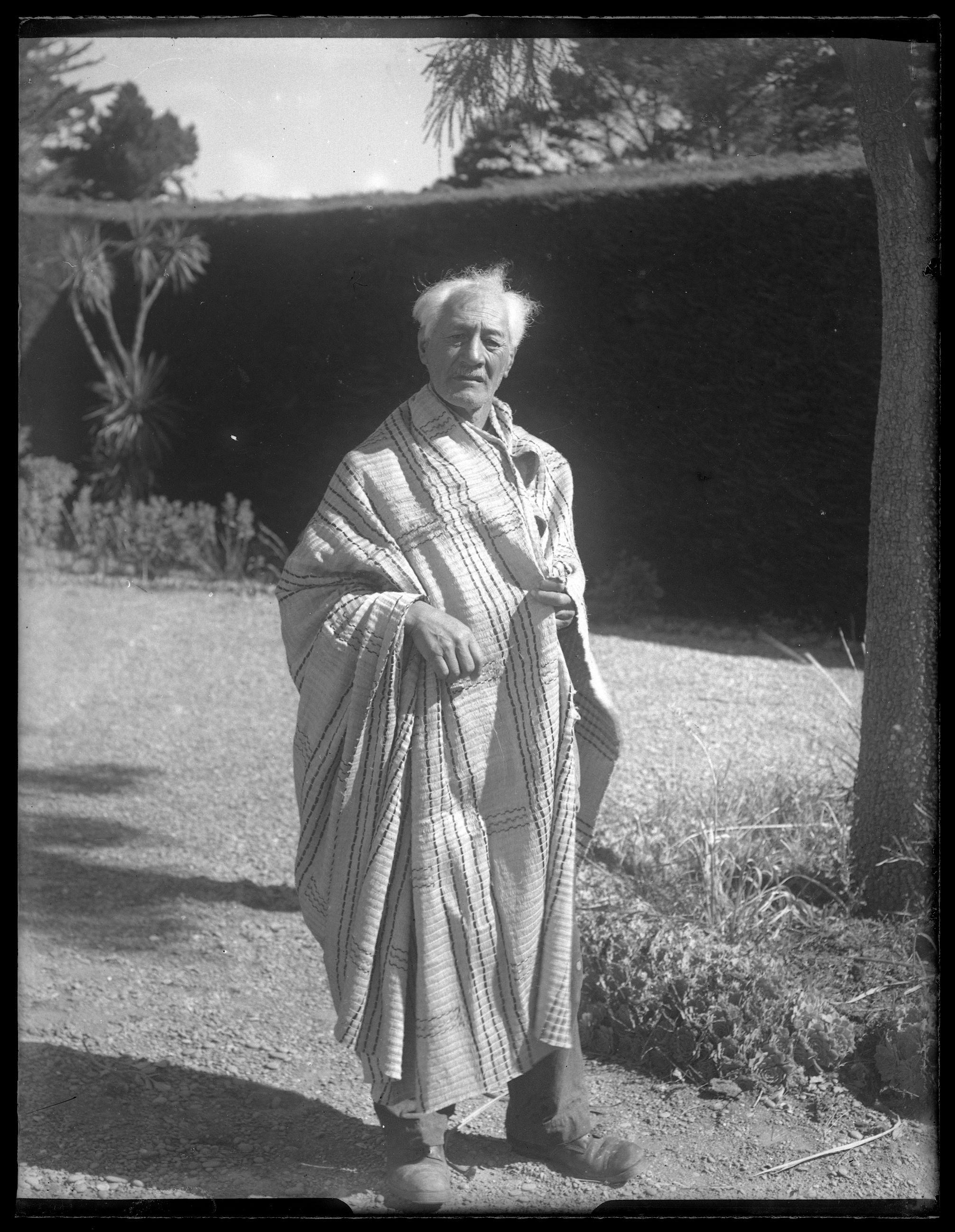

Hori Kerei Taiaroa

Hori Kerei Taiaroa (Ngāi Tahu) was born at Ōtākou in the 1830s or early 1840s. His father was the Ngāi Tahu chief Te Matenga Taiaroa and his mother was Mawera of Ngāti Rangiwhakaputa. He married Tini Pana (Jane Burns) whose mother was of Ngāi Tūāhuriri. In accordance with his father's wishes, Taiaroa made the pursuit of Te Kerēme, his life's work. In 1875 he was granted a tribal mandate to lead this mahi on behalf of the iwi.

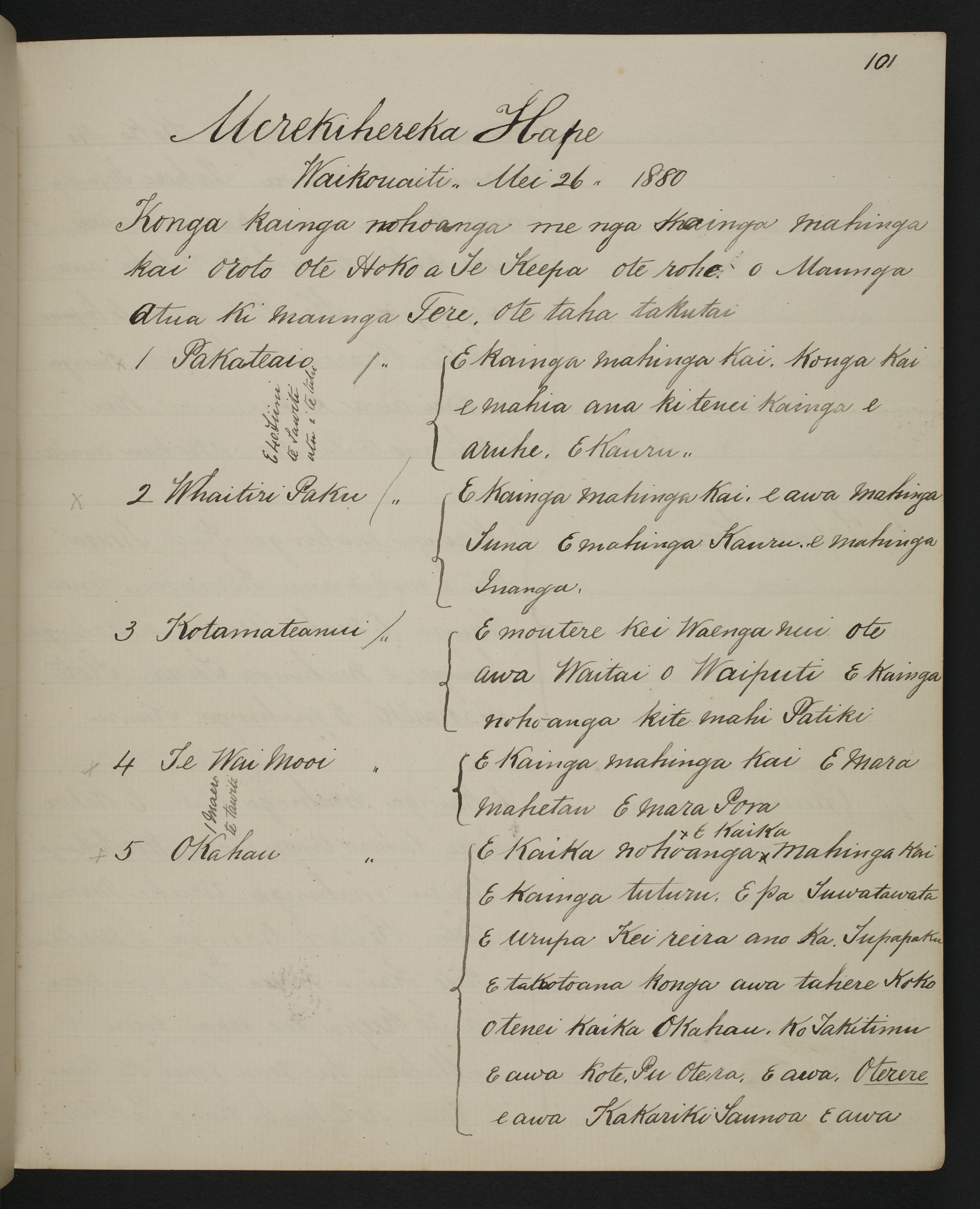

During his tenure as parliamentary representative for Southern Maori and on the Legislative Council he pushed for a series of inquiries into grievances arising from the Ngāi Tahu land purchases including the Smith-Nairn commission of inquiry which spurred the creation of the 1880 map. He was an outspoken critic of the government and vigorously advanced the Ngāi Tahu cause in Parliament in an often-lonely battle against impossible odds. He died at Wellington on 4 August 1905 and was buried in the churchyard at Ōtākou.