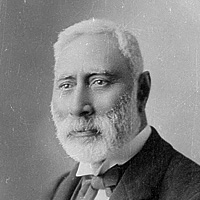

A meeting of Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Māmoe representatives at Te Hapa o Niu Tireni, Arowhenua in 1907 to discuss the recent South Island Landless Natives Act. This hui regenerated tribal efforts to advance Te Kerēme (the Ngāi Tahu Claim). Christchurch City Libraries Collection, Ngāi Tahu Archive, CD07-IMG0010.

Ngāi Tahu Whānui

Ngāi Tahu whānui is the collective of the individuals who descend from the primary tribal groups described as Waitaha, Ngāti Māmoe, and Ngāi Tahu. Ngāi Tahu also acknowledge our whakapapa to earlier iwi who occupied Te Waipounamu prior to the Ngāi Tahu migration to Te Waipounamu, including Kāti Hāwea, Kāti Wairaki and Te Rapuwai.

The name Waitaha is used to denote those people who descend directly from the Waitaha ancestor Rākaihautū, who landed in the great voyaging waka, Uruao, near Whakatū (Nelson) in ancient times. Our traditions place him and his people as the first human settlers in Te Waipounamu. Upon arriving at Whakatū, Rākaihautū divided the new arrivals into two groups; his son, Rakihouia, taking one party to explore the coastline, and Rākaihautū himself leading another party to explore inland. Rākaihautū led his travel party down the interior of the island to Murihiku (Southland), and then back along the eastern coastline. By using his kō (a Polynesian digging stick) named Tūwhakaroria, Rākaihautū dug the freshwater lakes of Te Waipounamu. After his work was completed, Rākaihautū renamed his kō “Tuhiraki”, and placed it on a hill in Akaroa Harbour.

Ngāti Māmoe descend from an ancestor who is known as both Hotu Māmoe and Whatua Māmoe. These people coalesced into a tribe in the late 15th century, centred on the two great pā, Ōtātara and Heipipi, near Ahuriri (now Napier). In the late 16th or early 17th century, a small migrant group of these people settled at Te Rimurapa (Sinclair Head) on the Raukawa Moana (Cook Strait) coast before migrating to Te Waipounamu where they established the renowned Waipapa pā at the mouth of the Waiautoa (Clarence River) on the Kaikōura coastline.

The arrival of Ngāi Tahu to Te Waipounamu is more complex. In the early to mid-17th Century Ngāi Tūhaitara and Ngāti Kurī, both hapū (sub-tribes) of what would later become Ngāi Tahu, settled at Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington) under the respective leadership of Tūāhuriri and Marukaitātea. Ngāti Kurī was the first tribal grouping to migrate to Te Waipounamu, establishing themselves at Kaikōura. Tūrākautahi, the son of Tūāhuriri, established Ngāi Tūhaitara at Te Kōhaka-a-kaikai-a-waro, commonly referred to as Kaiapoi pā. With Kaikōura and Kaiapoi pā established, Ngāi Tahu whānui progressively established manawhenua (tribal authority) in Te Waipounamu.

Over the following two generations there was regular fighting between Ngāti Māmoe and Ngāi Tahu, and even amongst Ngāi Tahu themselves. All this fighting was accompanied by an equal amount of intermarriage, population expansion and dispersal. As a consequence, careful study of our whakapapa shows that we were being welded into one interconnected people throughout the eighteenth century.

“This was the command thy love laid upon these Governors. That the law be made one, that the commandments be made one; That the nation be made one, that the white skin be made just as equal with the dark skin.”

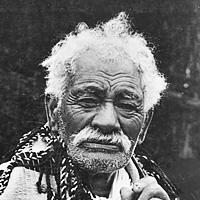

Matiaha Tiramōrehu, Petition to Queen Victoria, 6 September 1857

“These are the things which divide the Māoris from the Europeans. They feel that the promises made by the Europeans have not been fulfilled, while all that the Māori have promised has been fulfilled.”

Hori Kerei Taiaroa, MHR speaking in NZ Parliament, 21 October 1878

"A large number of Kaumatuas have gone to the land from whose bourne no traveller will ever return and we, the younger people, have been endeavouring to get some finality in connection with this claim . . . by finalising this matter you will give us great relief because most of us are poverty-stricken people."

Hoani Matiu, Part of Ngāi Tahu Deputation to Parliament, 4 October 1935

Te Kerēme

When the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840 by seven high-ranking Ngāi Tahu rangatira (chiefs), it was seen as a convenient arrangement between equals. The majority of Te Waipounamu was then purchased by the settler government from Ngāi Tahu in a series of ten land purchases between 1844 and 1863. The largest was the 1848 Canterbury Purchase, commonly known as Kemp’s Deed. Ngāi Tahu believed that the land sales would guarantee their own usage rights to the resources in the region and strengthen robust political, economic and social relationships with newcomers.

The government failed to honour their obligations under the land purchase agreements — such as the allocation of adequate reserves, protection of mahinga kai, paying a fair price for the purchased land, and the provision of schools and hospitals. Ngāi Tahu were robbed of the opportunity to participate in the land-based economy alongside the settlers, and were made virtually landless.

In 1849 Matiaha Tiramōrehu made the first formal statement of Ngāi Tahu grievances about the land purchases. His letter to Lieutenant Governor Eyre sought the Crown to set aside adequate reserves of land for the iwi as agreed to under the terms of its land purchases. Tiramōrehu sent a second letter to Queen Victoria in 1857 with the support of all of the leading Ngāi Tahu rangatira at the time. Despite various committees and commissions of inquiries upholding many of the Ngāi Tahu grievances, this was the beginning of generations of Ngāi Tahu petitioning the government over the following 150 years.

Overview of Te Kerēme

View videoThe Ngāi Tahu Settlement

In 1975 the New Zealand Government established the Waitangi Tribunal to investigate breaches made by the Crown in relation to the Treaty of Waitangi that had occurred since the Tribunal’s establishment. It wasn’t until 1985 that the Tribunal’s jurisdiction was extended to hear claims about any alleged breach of the Treaty since 1840. The following year the Ngaitahu Maori Trust Board lodged the Ngāi Tahu Claim with the Waitangi Tribunal to hear its grievances.

The Ngāi Tahu Claim was to be the largest claim heard by the Tribunal. Over the following three years the Ngaitahu Maori Trust Board undertook a powerhouse of work with historians and Ngāi Tahu whānui collating a wealth of information on Ngāi Tahu lands, histories and traditions. The evidence was presented in nine parts that Ngāi Tahu named as “The Nine Tall Trees”. Each of the first eight trees represented a different area of land purchased from the tribe, with the ninth tree representing mahinga kai. This evidence was presented to the Tribunal in over thirty hearings that occurred over a three-year period in different locations throughout Te Waipounamu.

The Tribunal ruled that it could not avoid the conclusion that in acquiring 34.5 million acres of land from Ngāi Tahu for £14,750 pounds, and leaving Ngāi Tahu with only 35,757 acres, the Crown had acted unconscionably and in repeated breach of the Treaty of Waitangi, and that consequently Ngāi Tahu suffered grave injustice over more than 140 years. The Tribunal recommended that Ngāi Tahu was entitled to substantial compensation from the Crown.

With the Crown accepting the thrust of the Waitangi Tribunal’s 1991 Ngāi Tahu Land Report, the Crown and Ngāi Tahu entered into negotiations. The findings of the Waitangi Tribunal and subsequent studies showed that the Ngāi Tahu losses arising from the Crown’s failure to honour its contractual duties were enormous. Although Ngāi Tahu understood that it could not receive full compensation from the Crown for its loss, Ngāi Tahu entered into negotiations from 1991 to 1994. Negotiations broke down in mid 1994, and were not resumed until the intervention of the Prime Minister Jim Bolger in 1996, culminating in the 1998 Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act.

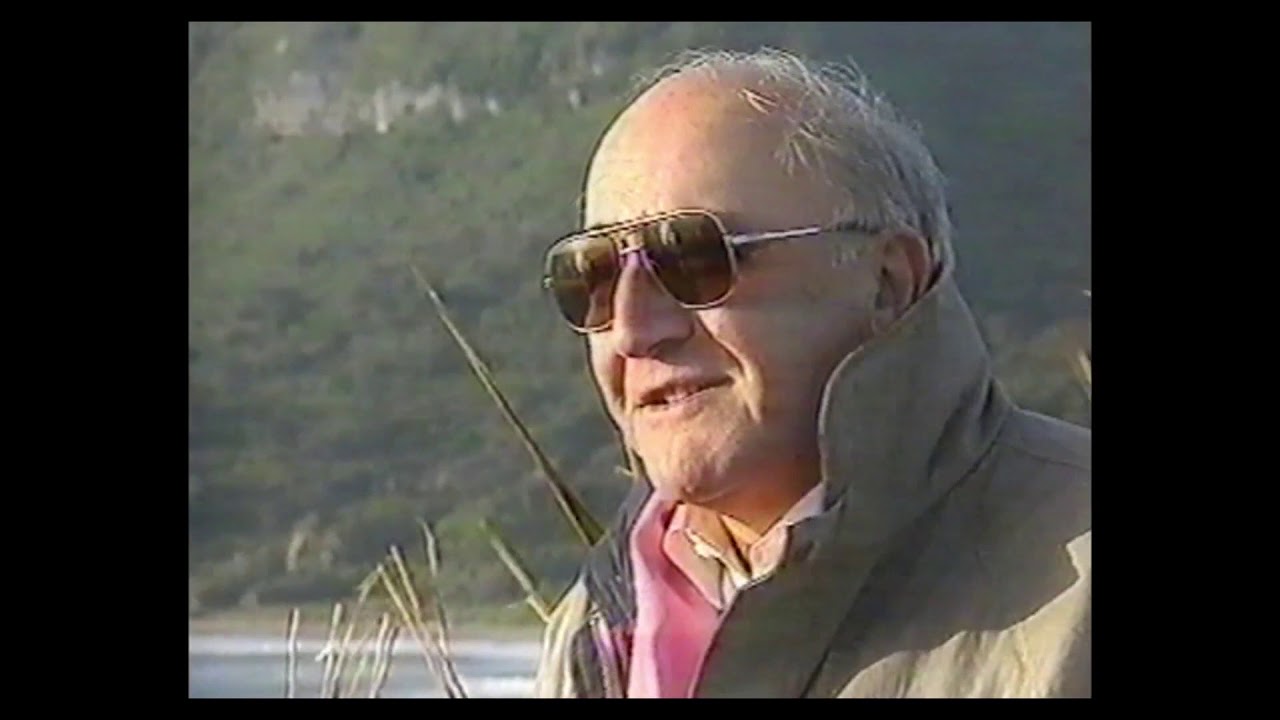

Historian Jim McAloon presenting evidence on the Murihiku (Southland) Purchase on behalf of Ngāi Tahu Whānui to the Waitangi Tribunal at the Fifth Hearing of the Ngāi Tahu Claim at Te Rau Aroha Marae, Awarua (Bluff), 1-3 February 1988. Ngaitahu Maori Trust Board Collection, Ngāi Tahu Archive, 2013.P.943

“I think the Claim takes hold of you. You don’t take hold of it. It’s like it knocks on the door and is inside your heart and your head and that’s it.”

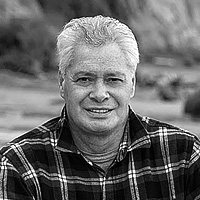

Jane Davis, 2016

“In the timeframe of the Claim, we didn’t have enough time to use all the information we gathered. We certainly didn’t have the technology that is now available to us.”

Trevor Howse, 2012

“A lot of people have asked me what cultural mapping is all about, and it is about gathering all that knowledge and those traditions and histories of our people across the whole rohe that we weren’t able to collect and collate during the prosecution of the Claim.”

David Higgins, 2015

Te Kerēme - The Ngāi Tahu Claim

View galleryContinue the Journey

Chapter Two – Protecting Ngāi Tahu History