Manuhaea was a kāinga nohoanga (seasonal settlement) located on the eastern side of “The Neck” at Lake Hāwea that was renowned for a small lagoon where tuna (eels) were gathered. The lagoon was submerged when Lake Hāwea was artificially raised in 1958 to store water for hydroelectric power generation. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Collection, Ngāi Tahu Archive, 2014-129-005

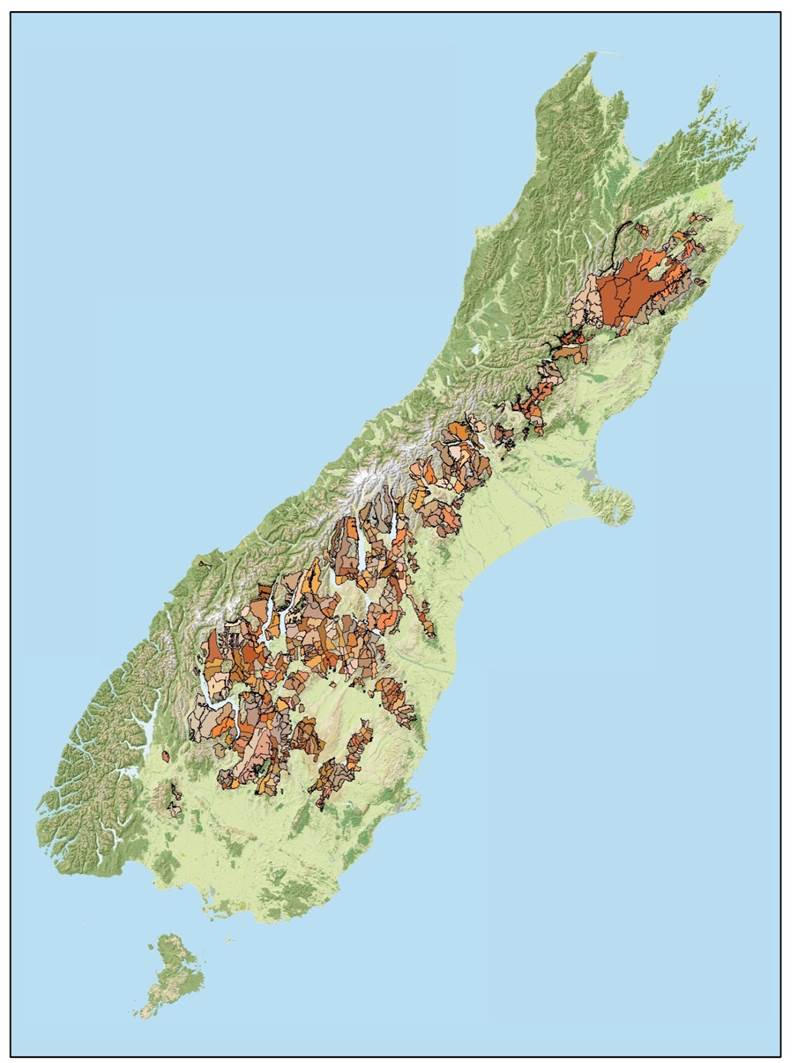

Protecting Ngāi Tahu interests on South Island high country pastoral leases through Tenure Review was the catalyst for establishing Kā Huru Manu. Tenure Review is a voluntary process that gives pastoral lessees an opportunity to buy some of their high country leasehold land, with the rest of land retained in Crown ownership, usually for conservation purposes.

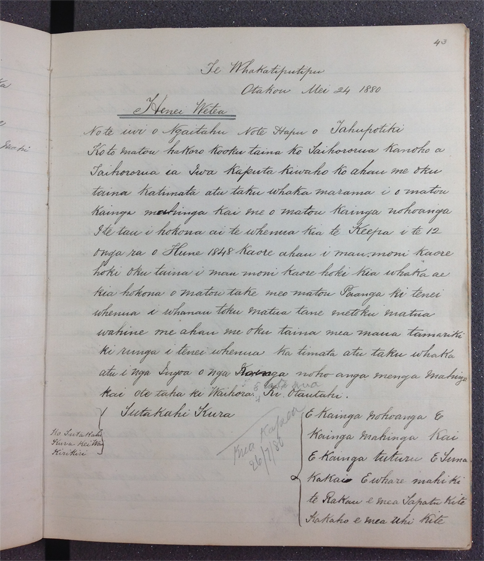

In the mid 19th Century the Crown asserted ownership of the South Island high country, despite the contradicting view of Ngāi Tahu. The inland boundary of the 1848 Crown purchase of the Canterbury and Otago area, commonly known as Kemp’s Deed, was not well-defined and the exact area purchased has always been a contentious issue. The inland boundary agreed to was from Maukatere (Mount Grey) in North Canterbury and along the foothills to Mauka Atua in Otago. Everything inland from the foothills was to remain in Ngāi Tahu ownership. Nevertheless, the Crown asserted ownership from the eastern coastline to the Main Divide. The area between the foothills and the Main Divide became known to Ngāi Tahu as “The Hole in the Middle”, to reflect the Ngāi Tahu opinion that this high country land was never sold.

“The ‘Hole in the Middle’ has been around on the Ngāi Tahu agenda for generations. Essentially it’s created by an argument about the inland boundary of the Kemp Purchase.” Tā Tipene O’Regan.

Tenure Review

After the Crown asserted ownership of the high country it established non-freeholding grazing licences in 1858. These licences were for Crown-owned land that was leased for pastoral farming for various fixed terms. The 1948 Land Act created a special category of pastoral land and offered more secure fixed-term leases, to be leased in perpetuity subject to certain conditions. The rationale was to incentivise greater investment into the land by providing increased security of tenure.

In the 1980s, leaseholders wanted to diversify their pastoral leases but were restricted under the provisions of the Land Act. Subsequently the Crown created Tenure Review, to provide leaseholders the opportunity to freehold those parts of the pastoral lease considered capable of economic development. Those parts of the pastoral lease containing “Significant Inherent Values” could be protected, usually through retention in Crown ownership as Conservation Areas.

The Ngaitahu Maori Trust Board was initially responsible for protecting Ngāi Tahu interests on the high country pastoral leases. This responsibility was transferred to its successor, Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu. In 2001 Ngāi Tahu and Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) formalised a protocol outlining Ngāi Tahu involvement in Tenure Review, allowing Ngāi Tahu representatives to inspect pastoral leases and to identify and recommend the protection and access of Ngāi Tahu cultural values.

Inspecting Pastoral Leases

View galleryManuhaea

In 2002 kaitiaki Papatipu Rūnaka recommended that as part of the Tenure Review process the Crown protect an area of culturally significant land associated with Manuhaea. The tribally well-known kāinga nohoanga (settlement) and kāinga mahinga kai (food-gathering place) is located on the eastern side of “The Neck”, the narrow isthmus of land separating lakes Hāwea and Wānaka. Manuhaea was renowned for a small lagoon where tuna (eels) were gathered. Other foods gathered at Manuhaea included weka, kākāpō, kiwi, kea, kākā, kererū and tūī; there were also potato, turnip, and kāuru māra (gardens).

Manuhaea was one of the kāinga attacked by Te Pūoho during the 1836 Ngāti Tama southern attack on Ngāi Tahu. The inhabitants escaped over Ōmakō (the Lindis Pass) and down the Waitaki River. One of the survivors, Rāwiri Te Maire, became an invaluable source of information on the Ngāi Tahu history of the interior of Te Waipounamu. In 1868 a 100 hectare fishery easement was allocated by the Native Land Court, abutting the lagoon at Manuhaea.

Despite the cultural and historical significance of Manuhaea, the lagoon and part of the fishery easement were submerged when Lake Hāwea was artificially raised in 1958 to store water for hydroelectric power generation.

Later, as part of the Tenure Review process, LINZ required Ngāi Tahu to provide yet further evidence of the cultural and historical significance of Manuhaea, in order to justify its protection. After working with kaitiaki Papatipu Rūnaka representatives and Matapura Ellison in his role as Kaupapa Atawhai Manager, kaumātua Trevor Howse, David Higgins and Kelly Davis were approached for support. With their assistance and that of the Papatipu Rūnaka representatives Ngāi Tahu was able to provide LINZ with the necessary historical information to set aside land at Manuhaea as a Conservation Area.

The Manuhaea kāinga was situated between the small lagoon in the background and Lake Hāwea. The lagoon, renowned for tuna (eels), was flooded when the lake was artificially raised in 1958 to store water for hydroelectric power generation. The tents are part of the public works camp that housed workers who constructed the road to Makarore (Makarora). Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu Collection, Ngāi Tahu Archive, 2017-0271

“E kāinga nohoanga, e mahinga kai, e mara mahetau, e mara pora, e mara kāuru. E tū ngā whare whakairo, e tū ngā whata pu kei reira anō ngā pou o ngā whare. Ko ngā manu, e weka, e kākāpō, e kiwi, e kea, e kākā, e kererū e koko me tahi a tū manu.”

Evidence of Ngāi Tahu kaumātua for Manuhaea presented to the 1879 Smith-Nairn Royal Commission of Inquiry

“Manuhaea is a place where we can stand. We want this to recreate our manawhenua at this time so we can illustrate our manawhenua. It’s our mana. Its nobody else’s.”

Kelly Davis, 2004

A settlement. Food gathering. Gardens of potato, turnip and kāuru (Cordyline). Emplacement of a carved house. Emplacement of a [pū] food store. The poles of the houses are still there. It is a sacred place. The birds are weka, kākāpō, kiwi, kea, kākā, wood pigeon, tūī and other birds.

Evidence of Ngāi Tahu kaumātua for Manuhaea presented to the 1879 Smith-Nairn Royal Commission of Inquiry

‘Die in the Ditch’ Areas

Although Manuhaea was a significant accomplishment, it highlighted the urgent need for Ngāi Tahu to be proactive in identifying and protecting cultural values on high country pastoral leases. Papatipu Rūnaka representatives were also becoming increasingly frustrated that Ngāi Tahu participation in Tenure Review was being largely determined by the Crown and driven by their conservation values.

The solution identified with Papatipu Rūnaka representatives to address these issues was to research and map Ngāi Tahu cultural values throughout the high country. This approach would assist Papatipu Rūnaka representatives to identify and protect key ‘die in the ditch’ areas situated on the high country pastoral leases. It would also provide the opportunity for Ngāi Tahu to build a storehouse of knowledge that could be used to ensure that cultural values were at the forefront of Ngāi Tahu participation in Tenure Review.

"The culture mapping process came out of that desire to empower our people to understand the landscape they were moving into."

Matapura Ellison, Puketeraki, 2015

Die in the Ditch Areas

View videoContinue the Journey

Chapter Three – Cultural Mapping Project Begins