Pounamu, also known as greenstone, jade or nephrite, was one of the most treasured of all natural resources for Māori. Adzes, chisels, knives and weapons of pounamu lifted the material condition of our ancestors onto another developmental plane.

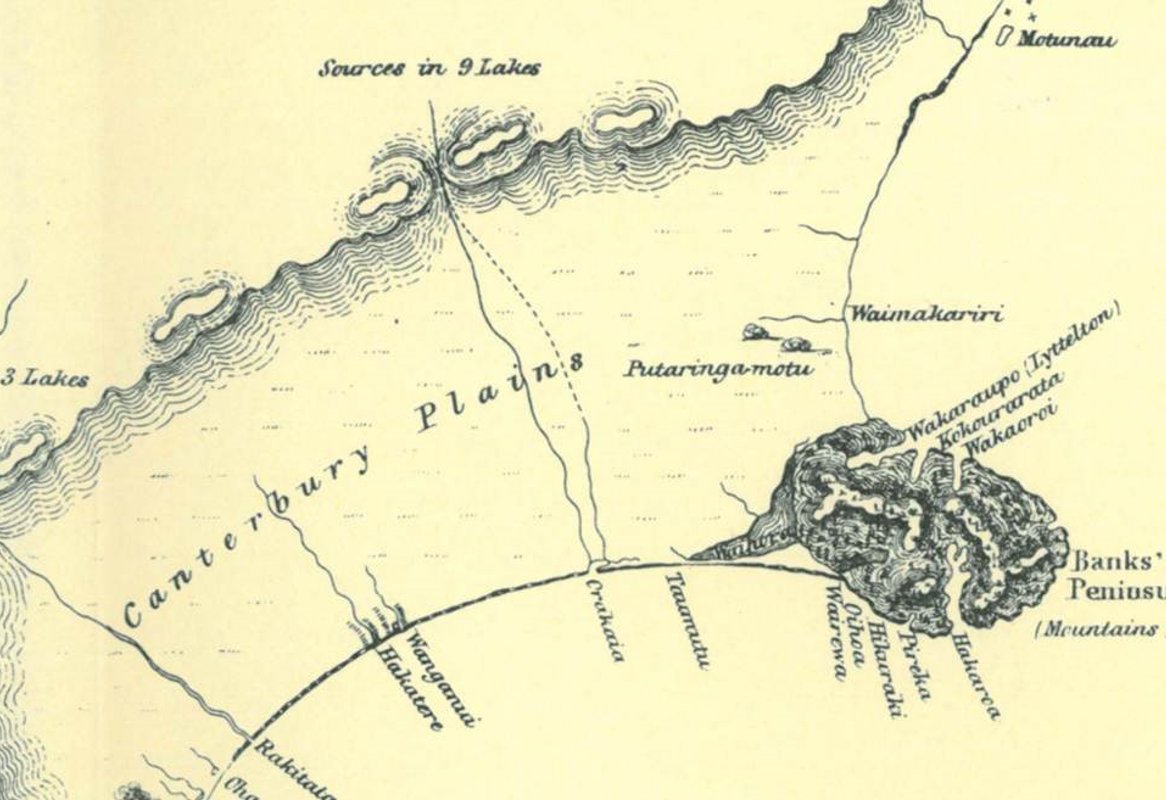

By the time Ngāi Tahu gained control of Canterbury and Horomaka/Te Pātaka-a-Rākaihautū (Banks Peninsula), Te Tai Poutini had been occupied for some generations by Kāti Wairaki who controlled the pounamu trade throughout Te Waipounamu. Kāti Wairaki transported pounamu along the west coast to the Nelson area and from there to Whanganui and into the North Island’s main pounamu trading centres.

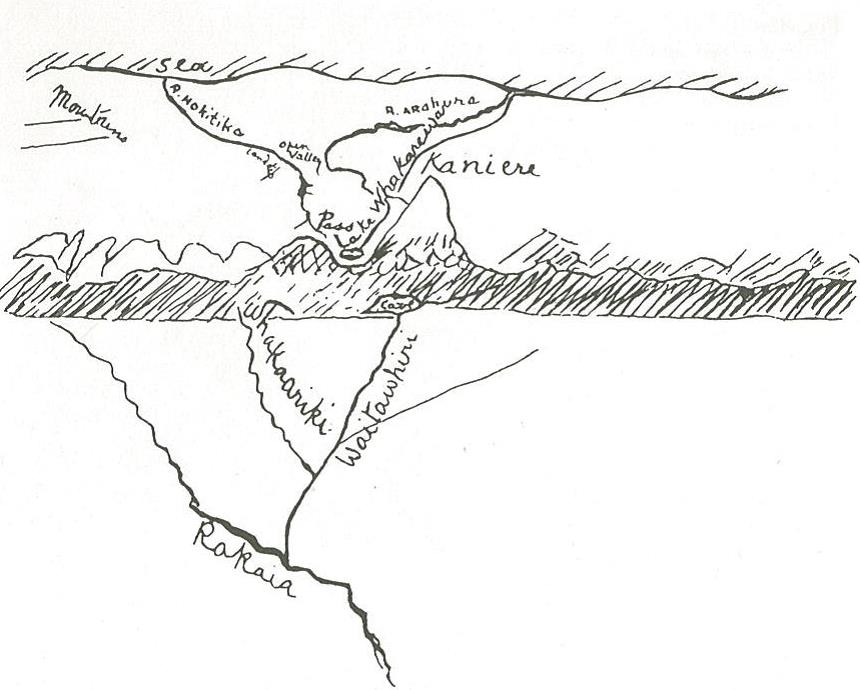

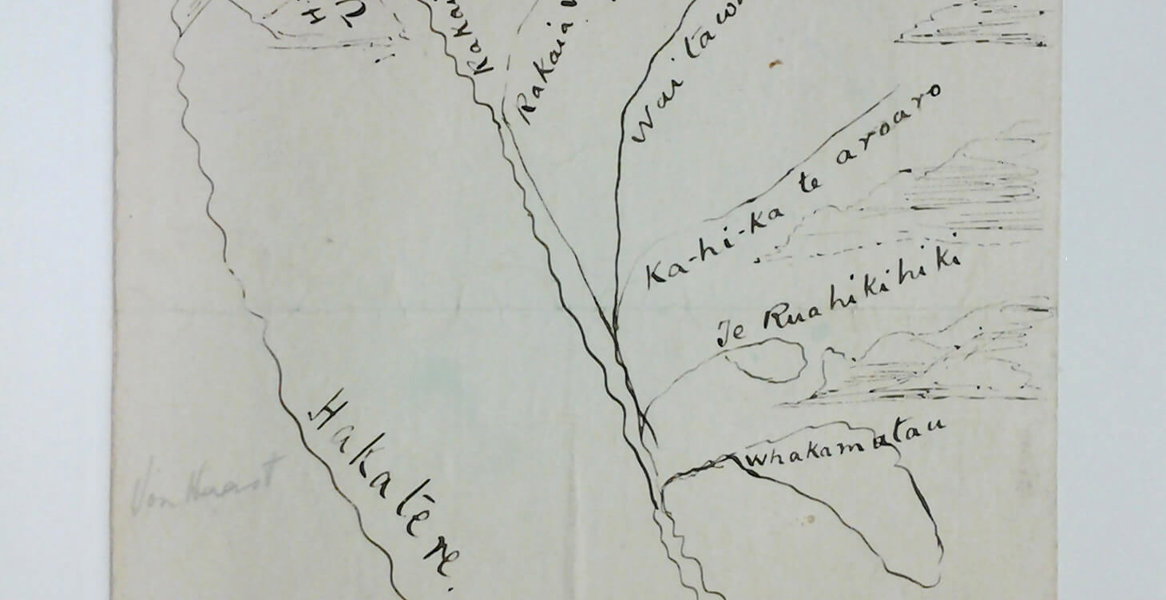

The revelation of the pass at the head of the Rakaia River is traditionally accorded to the arrival on the east coast of a Kāti Wairaki woman named Raureka. Born at the old settlement of Lake Kaniere, Raureka found her way across Kā Tiritiri-o-Te-Moana (the Southern Alps) carrying with her a pounamu toki (adze). On arrival in the Arowhenua region she was met and cared for by a party of Kāi Tūhaitara to whom she demonstrated the superiority of her stone tool. More importantly she revealed the route she had taken and provoked further exploration of the foothills and the route itself.

It was the knowledge of the route that was of first importance. Tūhaitara knew of the pounamu and its superiority. What they wanted to know was how to get to it. The detailed explanation of the route by Raureka is the key traditional event which led to the further exploration and later utilisation of the region not simply as a trade route but as a major resource zone in its own right.

The story of Raureka and the discovery of pounamu was depicted in South Canterbury Saga, a film made by Folio Films in 1952 to commemorate the Timaru Centennial. The film features Ngāi Tahu whānau members as the cast and was filmed on the banks of the Ōpihi River.